Harper Collins’ recent publication is an excellent cultural history of the phallus. Authored by Alka Pande and with contributions from Johan Mattelaer, Philip Van Kerrebroeck and Amrita Narayan – this new book, Pha(bu)llus, carries a list of nuanced essays and exciting images that give details about the plethora of ways in which the phallus has been perceived throughout human history. The studies in this edition span across regions and also shift the academic lens from one discipline to another while examining the cultural past(s) of the phallus.

Alka Pande expounds upon the fact that there is “an immersive, seductive, sensual and cultural journey of this part of the human body” and that depending on the location and religion of diverse societies, the phallus has transformed and gotten “its own unique cultural identity”. These identities have been fluid – sometimes erotic, sometimes sacred and sometimes both. It also transforms in ways that it can become both a source of power and pleasure and also a place of shame.

With detailed sections that deal with the phallus’ ‘erotic, symbolic, religious, cultural, psychological and pop cultural’ meanings, Pande’s introduction lucidly untangles the aim of the book – to explore the intricate network of ideas and beliefs surrounding the phallus and to dig a little deeper to understand “what is perhaps the most recognized cultural motif in the history of the human race”.

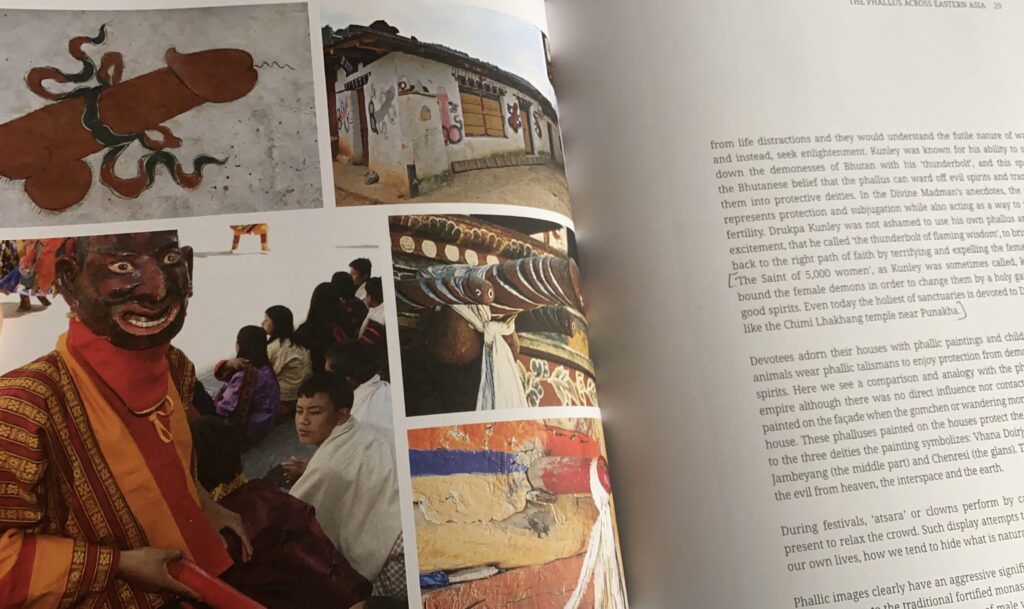

Johan Mattelaer explores the history of the phallus in regions across Asia and Europe. Looking at festivals celebrating phallic culture in places like Bhutan, he picks up examples of ‘astara’ or clowns that perform by carrying a phallus and that their presence is to “relax the crowd”. This, Mattelaer believes, is an attempt to explain “the naked truth of our own lives, how we tend to hide what is natural”. While there is a ‘relaxed imagery’ associated with the phallus, there also seems to be a sense of ‘aggressive significance’ – with gatekeepers (dwarapala) in the shape of male warriors with their power possessed in the phallus “as a living symbol”.

Mattelaer has also looked at the association of the phallus with creation myths. He retells the Japanese legend of Izanagi and Izanami in which they plant a giant phallus in the belly of the earth and use it like a spear to descend. The spear transforms into a tree of life and Izanagi and Izanami dance around it and at the end ‘imitate the story of the creation’, they make love and create islands. Stories like these show the relation between the sacred and the sensual.

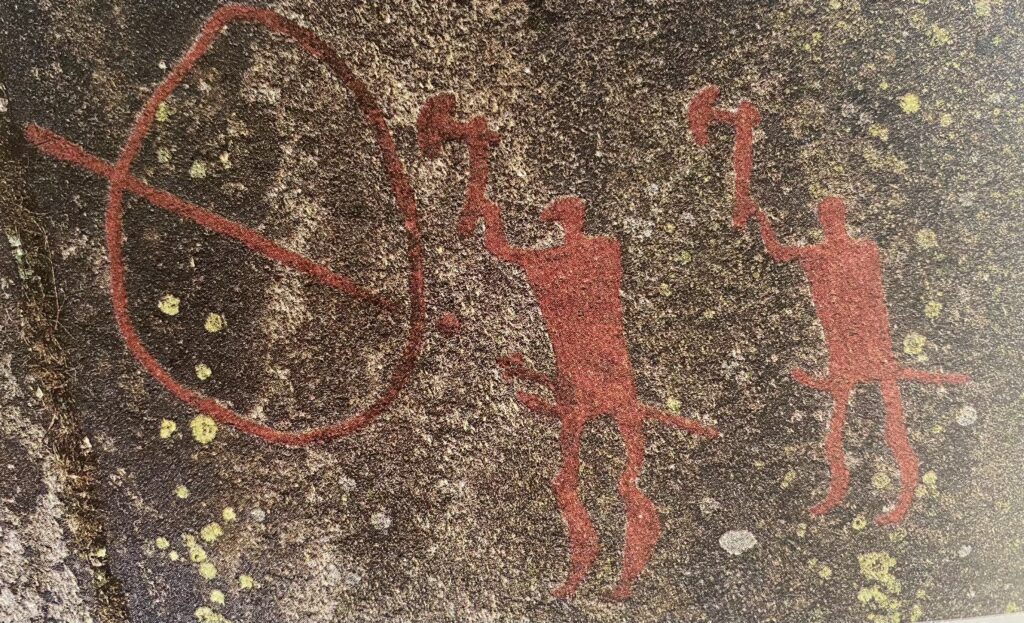

Through the examples of European prehistoric art, Mattelaer has also shown readers that “much of what the phallic symbol represents has nothing to do with the sexual act itself – strength in combat, for example, or skill in hunting or good luck at sea. This is highlighted very clearly in the Stone Age drawings in Bohuslan in southern Sweden and Bardal in Norway. In these drawings, ithyphallic men are depicted in the midst of hunting scenes.”

Rock paintings from the Bronze Age in Fossum, Bohuslan, Sweden.

Quite excitingly, Amrita Narayanan explores the ‘the phallus in psychoanalysis’ – its definitions, fantasies and even the role that geography plays! Calling the phallus a symbolic construction common to many civilizations and cultures – Narayanan shows that the figurative representation of the phallus is one ‘fullness’ and since it is permanently engorged, it commands a “power in the human imagination far in excess of the reality of a penis.” Since psychoanalysis tells us that every fantasy covers up a reality, the phallus which becomes an “emblem of wholeness” is able to provide us “an imaginary relief from the inherent lack and incompleteness of the human condition and the impossibility of total fulfillment within a human life”.

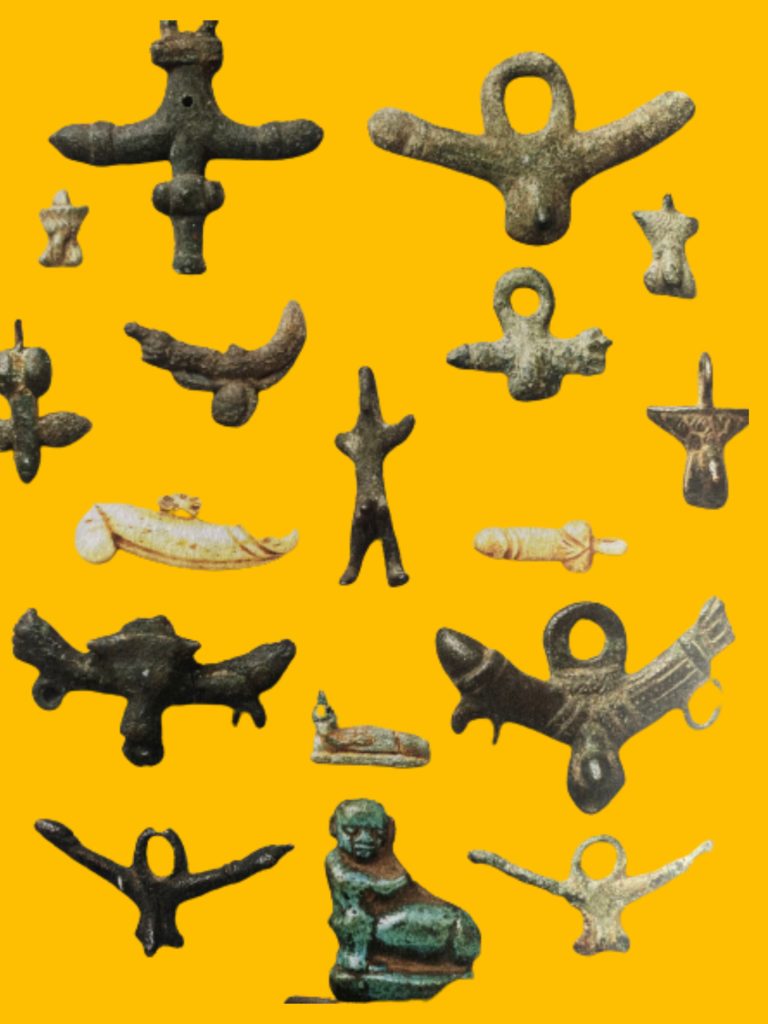

A collection of phallic amulets of Sigmund Freud

Philip Van Kerrebroeck has also made an exemplary contribution with his work on the worship of the phallus in indigienous societies and before examining the cultural symbols from Africa, North and South America and Oceania, Kerrebroeck remarks that “in order to appreciate the beauty and understand the importance and role of phallic objects” it is of importance that we study their place in the “framework of tribal arts in general, the ceremonial and religious nature of such art, the ceremonial and religious nature of such art, the subject and craftsmanship of these artefacts, and the specific visual and symbolic language they employ.”

The book also marks the rise and the decline of the ‘phallic culture’ and records that the “penis and the phallus both emerged from the shadow and the taboo placed on them in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries” while also noting the fact that though the re-emergence occurred, “the phallus never regained the wider significance of fertility and religious symbol…and the phallus only had erotic and sexual signifiance”. This has been explained through picking examples of the history of phallus in Europe and the presence of it in erotic and modern art of the day.

Pha(bu)llus has done an astounding job in giving a summary of the cultural history of phallus – stretching back to the prehistoric times and coming all the way down to the modern. With the vast geographies it covers and the diverse set of areas it taps into to examine the significance of the phallus – the book proves to be an exemplary addition to the Intimacy Curator Library!

If you have not purchased your copy yet, you can do so here.

This is a really interesting and well-written piece! Thoroughly enjoyed it.

Looks very interesting. Want to read the book!

excellently reviewed – builds a lot of interest in prospective readers! looking forward 🙂

A really good read! Damn interesting 💖

Looking forward to reading this review